Rabbits and Rum

by Victoria Dailey

Most books with California themes fall into familiar of categories. Exploration, travel and history are notable for such classics as Manly’s Death Valley in ’49 and Horace Bell’s Reminiscences of a Ranger. California fiction includes some of the most well known books about the region—Ramona, McTeague and The Day of the Locust. Illustrated books, too, have become classics, among them, Mary Austin’s The Land of Little Rain, and Paul Landacre’s California Hills. But occasionally, a book defies all known categories and is an isolate, existing sui generis. Such a book is Particeps Criminis, The Story of a California Rabbit Drive by Ervin S. Chapman, published in 1910.

Most books with California themes fall into familiar of categories. Exploration, travel and history are notable for such classics as Manly’s Death Valley in ’49 and Horace Bell’s Reminiscences of a Ranger. California fiction includes some of the most well known books about the region—Ramona, McTeague and The Day of the Locust. Illustrated books, too, have become classics, among them, Mary Austin’s The Land of Little Rain, and Paul Landacre’s California Hills. But occasionally, a book defies all known categories and is an isolate, existing sui generis. Such a book is Particeps Criminis, The Story of a California Rabbit Drive by Ervin S. Chapman, published in 1910.

This book has long puzzled me, mainly because I did not know where to shelve my copy within my collection of Californiana; it didn’t quite fit into any category I had devised: historical accounts, travel narratives, memoirs, biography, flora, fiction or illustrated. I ultimately settled on this last category since the book has an attractive decorative cover and fine illustrations throughout by American illustrator Harry Graydon Partlow, but I was uneasy about this choice since Particeps Criminis is not essentially an illustrated book. It seemed out of place alongside Prescott Chaplin’s woodcut books and did not sit well near Florence Lundborg’s Rubaiyat or Landacre’s California Hills. But there it remained, odd and uncategorizable.

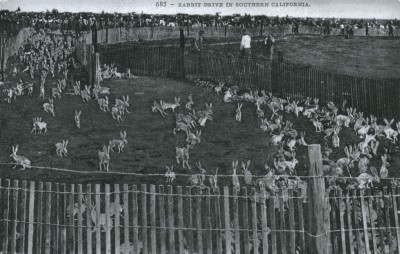

Furthermore, I could not solve the puzzle of its peculiar title. Was it a mystery story for boys with a rabbit as an accomplice to a crime? The adorable bunnies and innocent lads on the front cover suggested as much. I struggled to comprehend this bizarre book. I began to read it, and it seemed to be an account of the many rabbit drives that occurred in California during the years of settlement and expansion. Farmers had planted acres of crops where once had been brush and chaparral, and the native jackrabbit population increased mightily with this newfound food source. Their natural predators—coyotes—had suffered a decrease in numbers as settlers killed them off in an effort to protect their farm animals. Rabbits were endangering cash crops and they came to be regarded as pests requiring extermination.

Rabbit drives were devised as the preferred method to eradicate the furry creatures. Long, moveable fences were built along a stretch of open range or farmland. These fences were shaped into a large V, which funnelled thousands of the frightened creatures into a corral. Once inside the fenced area, the rabbits were slaughtered by men and boys with clubs—they beat the rabbits to death. In the San Joaquin Valley alone, at least 370,000 rabbits were killed between 1888 and 1895. Rabbit drives, followed by a barbecue or picnic, became popular town events throughout the growing state. They were covered regularly in the Los Angeles Times. One such headline bore the lenghty title “Rabbit Drive—Azusa People Clear Their Domain of the Pest. A Wild and Wooly Story of a Morning’s Sport—Hunters Armed With Prehistoric Weapons Slaughter Their Captives Without Mercy” [LAT August 21, 1893]. The drives even made their way into California fiction when Frank Norris chillingly described one in The Octopus (1901):

“The entire line, horses, buggies, wagons, gigs, dogs, men and boys on foot, and armed with clubs, moved slowly across the fields, sending up a cloud of white dust, that hung above the scene like smoke. A brisk gaiety was in the air. Everyone was in the best of humor, calling from team to team, laughing, skylarking, joshing…Gradually, the number of jacks to be seen over the expanse of stubble in front of the line of teams increased. Their antics were infinite. No two acted precisely alike…By noon the number of rabbits…was far into the thousands. What seemed to be ground resolved itself…into a maze of small, moving bodies, leaping, ducking, doubling, running back and forth—a wilderness of agitated ears, white tails and twinkling legs…As the day advanced, the rabbits, singularly enough, became less wild. When flushed, they no longer ran so far nor so fast, limping off instead a few feet at a time, and crouching down, their ears close upon their backs. Thus it was, that by degrees the teams began to close up on the main herd. At every instant the numbers increased. It was no longer thousands, it was tens of thousands. The earth was alive with rabbits…The line of vehicles was halted. To go forward now meant to trample the rabbits under foot. The drive came to a standstill while the herd entered the corral…The last stragglers went in with a rush, and the gate was dropped…On signal, the killing began…Armed with a club in each hand, the young fellows from Guadalajara and Bonneville, and the farm boys from the ranches, leaped over the rails of the corral. They walked unsteadily upon the myriad of crowding bodies underfoot, or, as space was cleared, sank almost waist deep into the mass that leaped and squirmed about them. Blindly, furiously, they struck and struck.”

Such brutality seems unthinkable today, yet it was accepted as necessary, beneficial even, to farmers intent on protecting their crops. In an historical irony, Norris’ unflinching account of the extermination of jackrabbits was published in 1901; the following year saw Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit, destined to become a classic, its lepine fable and adorable illustrations a bastion of early childhood literature. Particeps Criminis appeared eight years later.

Such brutality seems unthinkable today, yet it was accepted as necessary, beneficial even, to farmers intent on protecting their crops. In an historical irony, Norris’ unflinching account of the extermination of jackrabbits was published in 1901; the following year saw Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit, destined to become a classic, its lepine fable and adorable illustrations a bastion of early childhood literature. Particeps Criminis appeared eight years later.

Unlike Potter, Chapman’s book is filled with vignettes and chilling photos of rabbits being slaughtered. Chapter I begins with a description of a drive, which Chapman calls “thrillingly interesting.” But suddenly, Chapman makes a startling analogy: he compares the bunnies to innocent boys being driven into corrals of sin and death by alcohol. As he states: “I point out the startling resemblances between the details of a successful rabbit drive…and the details of the processes by which so many of our buoyant youth are hurried to a dismal destiny…The rabbit drive and the boy drive!…the most lovely and promising boys, as they advance to the estate of manhood, become helpless, degraded slaves of rum. They are driven into a condition of degradation and ruin.”

Particeps Criminis is a temperance book! No wonder I couldn’t place it on my shelves, that category being entirely unoccupied, let alone imagined. Unlikely as it seems, Chapman’s intent is to force the reader to acknowledge that the wholesale slaughter of bunnies is the equivalent of innocent boys being led to ruin by liquor. How did he come to make this shocking assertion, and just who was Ervin S. Chapman?

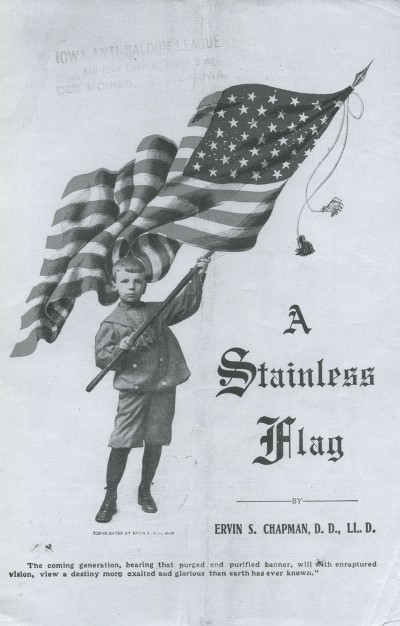

Born in 1838 in Ohio, Chapman served as a clerk in the U. S. House of Representatives in the 1860s, married an Ohio woman, Adelia Haymaker, in 1860, and was ordained as a minister in the United Brethren of Christ in 1872 after receiving degrees from divinity schools in the Midwest and East. Later transferring to the Presbyterian Church, he served as a pastor in Ohio, Wyoming and California, where he settled in Alameda about 1886. He became pastor at Mills College in the 1890s, lecturing throughout the state to wide acclaim for his inspiring sermons. He became active in temperance issues, and in 1898 Chapman became superintendent of the California Anti-Saloon League and editor of The Searchlight, its official magazine, dividing his time between the Bay Area and Los Angeles. In 1906 he authored the popular temperance tract, “A Stainless Flag,” which was based on an address he gave at a conference of 250 pastors in Los Angeles. Chapman then delivered the speech thirty times on a lecture tour of the country, and the pamphlet sold three million copies nationally. It was entered as evidence in a 1912 Senate subcommittee hearing taking evidence on the regulation of saloons and liquor.

Chapman seems always to have been fond of striking analogies. In “A Stainless Flag,” he compares an ivy vine growing against the wall of a large building to the sale of liquor, describing the vine as a “parasite, feeding upon prosperity but never producing it, a vicious poison ivy, freighting the air with the malignant germs of moral and material pestilence…” Let us accept that a morally questionable action can be compared to a strangulating vine, but how did Chapman come to equate rabbits with boys? That analogy seems far-fetched. An article that appeared in the August 18th, 1897 issue of the Los Angeles Times may hold a clue. Thirty-six boys from a state reform school in Whittier had escaped, and it made for a big news story. Titled “A Dash for Freedom,” the article begins: “There was a boy hunt at Whittier yesterday evening that in many respects resembled an old-fashioned rabbit drive.” The runaways hightailed it from the school and into neighboring fields of corn and pampas grass, most heading east for Los Angeles. At least a hundred men on horseback, on bicycles and in buggies, alerted by the school alarm whistle, began to hunt for the boys as a cordon was established around the fugitives. “A band of Mexicans joined in the chase on their bronchos and succeeded in capturing several of the youths. The reward money will keep the paisanos in mescal and cigarettes for a month.” All but three of the escapees were captured and they were sent to the school dungeon, where they faced punishment by whipping and a diet of bread and water.

Had Chapman read this article? Did it trigger an idea in his mind? It seems likely. By 1903, he expanded his popular temperance lectures to include descriptions of the rabbit drives. At a speech in Fullerton, Chapman stated that like rabbits, once boys are corralled into drunkenness, “escape from this hell is impossible.” (LAT, Feb. 2, 1903]. During a speech in Covina encouraging city officials to adopt dry laws, Chapman “prefaced his remarks by a graphic description of a rabbit drive in the San Joaquin Valley, when 10,000 of the little animals were destroyed in one day. Like these rabbits are the young men of California being driven into a corral not built of boards, but drunkenness, degradation and damnation, and this by influences largely outside of themselves, the open saloon, the treating habit, and the social club.” [LAT, May 12, 1903]

Temperance was a big issue in the 19th century; public drunkeness was common and the abuse suffered by women and children by inebriated husbands and fathers was widespread. Many thoughtful people advocated for the banning of alcohol, and legislation was passed in numerous municipalities prohibiting saloons and liquor sales. With the establishment of scores of new towns in Southern California in the 1880s and 1890s, “dry” laws went into effect in many of them. It is worth noting that many of the new settlers had arrived from such “dry” states as Maine, Iowa, Kansas and Massachusetts, and they brought their temperence beliefs with them. In 1887, Pasadena became the first city in California to outlaw saloons. Within months, Riverside and Monrovia followed suit. In 1888, South Pasadena, Long Beach, Orange, San Jacinto, Elsinore and Compton went dry; and in 1889, Escondido and Pomona passed similar laws. Coronado, owned and developed by the Elisha Babcock’s Coronado Beach Company in 1887-88, prohibited saloons in the fledgling town, but at its luxurious resort, the Hotel del Coronado, “the bar dispenses liquid refreshments at fancy prices.” It was the only place in town where alcohol was sold, and by 1909, the anti-saloon forces were so strong that it was feared the hotel would be forced to close. Chapman and his colleagues worked tirelessly for prohibition, and one anecdote serves to illustrated both Chapman’s character and the strength of his convictions. On a trip to Norfolk, Virginia to attend a meeting of the American Anti-Saloon league in 1907, Chapman said that he was “too busy to see anything of the historic old town except the part between his hotel and the place of holding the convention.” [LAT, Oct. 18, 1907]

Temperance was a big issue in the 19th century; public drunkeness was common and the abuse suffered by women and children by inebriated husbands and fathers was widespread. Many thoughtful people advocated for the banning of alcohol, and legislation was passed in numerous municipalities prohibiting saloons and liquor sales. With the establishment of scores of new towns in Southern California in the 1880s and 1890s, “dry” laws went into effect in many of them. It is worth noting that many of the new settlers had arrived from such “dry” states as Maine, Iowa, Kansas and Massachusetts, and they brought their temperence beliefs with them. In 1887, Pasadena became the first city in California to outlaw saloons. Within months, Riverside and Monrovia followed suit. In 1888, South Pasadena, Long Beach, Orange, San Jacinto, Elsinore and Compton went dry; and in 1889, Escondido and Pomona passed similar laws. Coronado, owned and developed by the Elisha Babcock’s Coronado Beach Company in 1887-88, prohibited saloons in the fledgling town, but at its luxurious resort, the Hotel del Coronado, “the bar dispenses liquid refreshments at fancy prices.” It was the only place in town where alcohol was sold, and by 1909, the anti-saloon forces were so strong that it was feared the hotel would be forced to close. Chapman and his colleagues worked tirelessly for prohibition, and one anecdote serves to illustrated both Chapman’s character and the strength of his convictions. On a trip to Norfolk, Virginia to attend a meeting of the American Anti-Saloon league in 1907, Chapman said that he was “too busy to see anything of the historic old town except the part between his hotel and the place of holding the convention.” [LAT, Oct. 18, 1907]

Such prohibition conventions were held throughout the country and prohibition candidates ran for office, winning in some districts. Ultimately, a measure made it on the California ballot in November 1914 which would have prohibited the sale of alcohol throughout the state, and similar propositions were on the ballot in Ohio, Colorado, Arizona, Oregon and Washington. With the exception of California and Ohio, the prohibition measures all passed, paving the way for the ultimate victory of the anti-alcohol forces nationwide in 1919 when the Volstead Act was passed.

When Rev. Chapman died in Los Angeles in 1921, he must have felt a great sense of accomplishment. His long crusade had ended in victory (at least until 1933). And my quest to categorize his book is over: Particeps Criminis is the first volume in my newly formed category of California temperance books. It will sit on my shelf awaiting its brethren…but a new question arises. Shall I place the temperance books near those on California wine? Would the bibliograpic proximity to Agoston Haraszthy, Frona Wait and E. H. Rixford make Rev. Chapman uneasy? Perhaps all tempers—wet and dry—can agree with a philosophical toast from Homer Simpson: “To Alcohol—the cause of and solution to all of life’s problems.”