Los Angeles In Tune

By Victoria Dailey

Before L. A. played itself in the movies, it was played as music when dozens of songs were written to praise and promote it during the period 1875-1955. Not only was Los Angeles advertised in brochures, postcards, posters, chinaware, spoons, citrus labels, buttons and books, it was promoted through waltzes, mazurkas, marches, galops, schottisches, tangos and quick steps. Tunes were written, some with whimsical titles, that described local landmarks, events or places, and much like the colorful citrus labels of the era, sheet music covers were designed to attract the eye. A tune might be catchy, but an evocative cover was an additional way to entice the customer, especially in the days before radio when all that a potential buyer had to rely on was a visual image–unless, or course, she had already heard the tune in a local performance–and opportunities to hear all sorts of music were plentiful in Los Angeles.

Before L. A. played itself in the movies, it was played as music when dozens of songs were written to praise and promote it during the period 1875-1955. Not only was Los Angeles advertised in brochures, postcards, posters, chinaware, spoons, citrus labels, buttons and books, it was promoted through waltzes, mazurkas, marches, galops, schottisches, tangos and quick steps. Tunes were written, some with whimsical titles, that described local landmarks, events or places, and much like the colorful citrus labels of the era, sheet music covers were designed to attract the eye. A tune might be catchy, but an evocative cover was an additional way to entice the customer, especially in the days before radio when all that a potential buyer had to rely on was a visual image–unless, or course, she had already heard the tune in a local performance–and opportunities to hear all sorts of music were plentiful in Los Angeles.

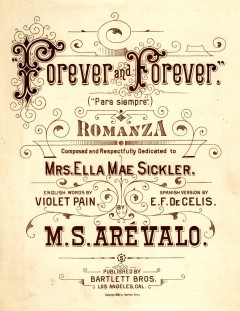

The city had a strong musical past, and while the visual arts took decades to coalesce–an art museum did not open until 1913–music was there from the beginning. Performances were often held in the homes of local grandees during the 1850s and ’60s, when Spanish and Mexican music was the natural focus for a traditionally Spanish-speaking population. Los Angeles was then a remote outpost accessible only by ship or stage and its small population lacked such urban luxuries as music printers. Music would have been performed from memory or from sheet music printed elsewhere. By the 1870s, when the first theaters opened, sheet music could be purchased at several bookstores in Los Angeles, but it had to be imported from San Francisco or the East–there was no local publishing other than newspapers and pamphlets. Manuel Arévalo (1843-1900), a Guadalajara-born guitarist and composer, arrived in town in 1871 and became one of Los Angeles’ leading performers, composers and teachers. Initially, although he advertised for students in one of the regional papers, his compositions were, of necessity, published in San Francisco. Later, in 1888, one of Arévalo’s songs was actually published in Los Angeles by Bartlett Brothers. Forever and Forever featured a cover designed in the wildly exuberant typographic style popular throughout the United States at the time and it would take several years more for regional themes to appear on sheet music covers. Similarly, the cover for the Annaheim [sic] Polka (c. 1875), one of the first pieces of music written about a Southern California town, is also in the prevailing American style of the day: its only nod to California is the depiction of the state seal. Another early regional song, a polka dedicated to Pasadena that was published in 1886, features a generic landscape on the cover. This early period did not reflect a regional visual style since it had yet to be developed, but within a decade, an entire visual vocabulary would evolve to describe the Southland as thousands of pieces of advertising and promotional material issued forth in a ceaseless campaign to attract tourists and settlers.

In a great stroke of fortune, the promotion of Southern California occurred just when commercial printing reached a technical and artistic peak, and California looked good in print. The promotional material during the years 1885-1940 portrayed the Golden State, and especially Southern California, in luscious colors, idealized images and elegant typography. Promoting California became one of the greatest and longest running advertising efforts of all time. Real estate developers, hotels, railroads, chambers of commerce and small businesses all competed to produce the most beautiful and lavish brochures, cards, posters and the like. No other locale has ever produced more promotional ephemera than California–not Paris, not Rome, not all of Europe combined; not Niagara Falls nor the Grand Canyon; not Florida, not Louisiana, not all of the other states combined. California, unique in so many ways, stands alone in the breadth of its promotional printed matter.

The printing bonanza of the 1890s in Southern California coincided with the region’s staggering growth that was precipitated by the publication of several travel books in the 1870s, the opening of a direct rail line from Chicago in 1885 and the reorganization of the Chamber of Commerce in 1888. The railroad companies and various nascent booster organizations began to inundate the country with promotional material and as a result, tourists and settlers began pouring in. Southern California, with Los Angeles as its star, promoted itself as a modern Eden whose resources were unending and whose promises seemed infinite. The city found a marketable identity in its most readily available substance, sunshine, and a visual image of Los Angeles began to emerge, separate from prevailing American styles. Although gold had been discovered in Northern California in 1848, it was the discovery of stellar gold a generation later that resulted in Southern California’s monumental rise. However, unlike the north, it was not miners or rough-and-ready roustabouts who made up a majority of the new immigrants; it was typically the well educated and well off. Many immigrants had sold their homes, farms and businesses in the East and Midwest and turned the proceeds into an orange grove and new home in Southern California. Since existing housing was scarce, settlers had to build their own homes or buy them from developers, requiring a sizable investment. While the ’49ers were content to live in tents or cabins while seeking their fortunes, the new residents of Southern California in the 1880s, having already made theirs, wanted picturesque new homes that reflected their prosperity and their faith in the region. The Southern California real estate mania was born, resulting in the great boom and consequent bust of the late 1880s, a cycle that has never subsided. One journalist marveled in 1887: “We doubt whether in the whole United States, so many intelligent and wealthy people could be found in the same area as found in Southern California.” These prosperous settlers caused Los Angeles and vicinity to develop in a way unlike any other region of the country. Los Angeles was a city, but also an agricultural center. One astute observer noted in 1876: “In appearance more like a series of gardens and country-places than a compact mass of houses, [Los Angeles] covers an area of 6 square miles. For purely local reasons, the city, instead of being a consumer is, oddly enough, a producer. The yearly production from land within the city limits is, in fact, so great that it will practically support the entire population.” Los Angeles with its vineyards, orange groves and flowers, was as close to paradise as anyone in the 19th century could imagine.

Because so many of the new Angelenos were well educated, prosperous, and familiar with many musical genres, they enthusiastically supported the building of new theaters and performance halls. The city’s first real theater, the Merced, opened in 1871 and was soon eclipsed by Wood’s Opera House in 1876 and the Grand Opera House in 1877, the second largest theatre on the Pacific Coast with 1200 seats and among the first anywhere to be lit by electricity. The 4000-seat Hazard’s Pavilion at Fifth and Olive opened in 1887 with a performance by the traveling National Opera Company, whose cast of 300 was a huge success; and by 1900, Los Angeles had come of age musically when Hazard’s was chosen as the venue for the American première of Puccini’s La Bohème. Managers and promoters could count on a good audience in the City of Angels.

In addition to all the musical theaters, there were hundreds of music and voice teachers in the Southland, attracted not just by the climate but also by a citizenry that avidly supported musical events and music lessons, which were considered obligatory for the children of the middle and upper classes. As a result, music schools sprang into existence, most prominently, The Los Angeles Conservatory of Music and Arts, which opened in 1883 and lasted well into the 20th century. Other music schools opened as well, among them, the fanciful California School of Artistic Whistling, which opened in 1905. Directed by professional whistler Agnes Woodward, the school gave recitals of classical and popular music as warbled by both soloists and choruses. Los Angeles was giddy with music, and with spreading the news of its phenomenal growth and success.

All the advertising worked. Los Angeles’ six thousand residents of 1870 had become three hundred and twenty thousand by 1910. Certainly, many settlers arrived under the spell of booster literature and the sound of lilting melodies. Southern California’s sunshine, and its attendant products–especially oranges, palms and flowers–became the iconographic shorthand for the region. They were perfect images for booklet covers, postcards and song sheets. Amongst all the printed matter, sheet music was perhaps the most subtle way to attract tourists: A song could be experienced directly, it could be sung or hummed, and the lyrics describing California’s physical attributes became part of the national psyche. In 1905, when the Salt Lake Route to Los Angeles was opened, the railroad published and gave away the sheet music for a hit tune with an emblematic theme, Through the Orange Groves of Southern California. A postcard of the same vintage has a nearly identical image. Similarly, When the Orange Trees are Blooming in the Valley of San Gabriel was unabashedly described by its publisher as a “Universal song hit…the greatest California song ever written” when it was published in 1913. Oranges, and songs about them, could be counted on to generate interest, and oranges appeared on thousands of examples of promotional material as the same images were printed, reprinted and reinterpreted for decades. Oranges, once a luxury product, were now readily available throughout the country thanks to California sunshine, industrious growers and a network of railroads, and they became the leading synonym for California. The Los Angeles Waltzes of 1905 features not only a group of oranges, but also, a palm tree, that other symbol of the region’s exotic atmosphere, and the simple combination of orange and palm told a potent story. Palms could be counted on to project an image of Southern California as part desert oasis, part Arabesque fantasy, part tropical paradise. Never mind that the predominant native trees were oaks and sycamores; pines and spruces; bays and cottonwoods; and that only one of all the 2,500 species of palms in the world is actually native to California, the California Fan Palm. It was relatively scarce, growing mainly in the Mojave Desert, but palms looked good in print and, like much other flora, they were planted throughout the region to satisfy not a need for shade or windscreen, but a need for fantasy. Because of its ability to sustain nearly all newcomers, the soil of the Los Angeles region accommodated the growth of thousands of immigrant trees, not just the palm and orange, but also, the eucalyptus, pepper, magnolia and jacaranda–but none has achieved the iconic status of the palm.

All the advertising worked. Los Angeles’ six thousand residents of 1870 had become three hundred and twenty thousand by 1910. Certainly, many settlers arrived under the spell of booster literature and the sound of lilting melodies. Southern California’s sunshine, and its attendant products–especially oranges, palms and flowers–became the iconographic shorthand for the region. They were perfect images for booklet covers, postcards and song sheets. Amongst all the printed matter, sheet music was perhaps the most subtle way to attract tourists: A song could be experienced directly, it could be sung or hummed, and the lyrics describing California’s physical attributes became part of the national psyche. In 1905, when the Salt Lake Route to Los Angeles was opened, the railroad published and gave away the sheet music for a hit tune with an emblematic theme, Through the Orange Groves of Southern California. A postcard of the same vintage has a nearly identical image. Similarly, When the Orange Trees are Blooming in the Valley of San Gabriel was unabashedly described by its publisher as a “Universal song hit…the greatest California song ever written” when it was published in 1913. Oranges, and songs about them, could be counted on to generate interest, and oranges appeared on thousands of examples of promotional material as the same images were printed, reprinted and reinterpreted for decades. Oranges, once a luxury product, were now readily available throughout the country thanks to California sunshine, industrious growers and a network of railroads, and they became the leading synonym for California. The Los Angeles Waltzes of 1905 features not only a group of oranges, but also, a palm tree, that other symbol of the region’s exotic atmosphere, and the simple combination of orange and palm told a potent story. Palms could be counted on to project an image of Southern California as part desert oasis, part Arabesque fantasy, part tropical paradise. Never mind that the predominant native trees were oaks and sycamores; pines and spruces; bays and cottonwoods; and that only one of all the 2,500 species of palms in the world is actually native to California, the California Fan Palm. It was relatively scarce, growing mainly in the Mojave Desert, but palms looked good in print and, like much other flora, they were planted throughout the region to satisfy not a need for shade or windscreen, but a need for fantasy. Because of its ability to sustain nearly all newcomers, the soil of the Los Angeles region accommodated the growth of thousands of immigrant trees, not just the palm and orange, but also, the eucalyptus, pepper, magnolia and jacaranda–but none has achieved the iconic status of the palm.

In 1915, the Southern California Booster Club (one of scores of such organizations) held a contest to determine who could write the best song about the region “in order to aid in its work of spreading the truth about Southern California.” John Zamecnik, a noted composer, won $2000 for the music, while Adele Humphrey, a local journalist and teacher, won $500 for her lyrics. The cover features palms, poppies and birds, all printed in orange. Apart from the cover, the lyrics emphasize what most of the promotional material of the day pictured: sunshine and flowers.

In the fertile, sunny Southland,

Where the sky is always blue,

Mountain sides and rolling valleys,

Blooming meadows fair to view,

Shelter homes of happy people,

In their lives supremely blest–

Days of sunshine nights of coolness,

Bring activity–then rest.

Of course, the most famous song to promote the idea of California was “California Here I Come,” written in 1921 and made famous by Al Jolson. In a version published in 1924, the cover features Jolson, oranges, and the Santa Barbara Mission. The refrain captures all that California embodied:

California, here I come–

Right back where I stated from–

Where bowers of flowers bloom in the sun–

Each morning at dawning,

Birdies sing an’ ev’ry thing.

Yet despite all the sunshine, birds, trees and flowers, the most enduring symbol of Southern California became a teenage girl, Ramona, the heroine of Helen Hunt Jackson’s novel of 1884, the first novel set in Southern California. Before publication of Ramona, Angelenos had a vague sense of their history, most of which they ignored, but the descriptions of the recent past, especially the scenes of a leisurely life on an old rancho–heavily romanticized by Jackson–made Angelenos embrace local traditions, including music. Music played a part in Jackson’s portrayal, as Alessandro, the hero of the novel, was a talented violin player and singer who serenaded Ramona just after they had met and whose violin was a prized possession. Suddenly, a Ramona-inspired craze made all things Mexican popular, from music and the restoration of the crumbling missions to the incorporation of Mexican food into local cuisine. Fiestas became fashionable, and Californians began to eat enchiladas. The Mexican era could be used as a marketing tool, and it wasn’t long before images of señoritas, vaqueros and missions began to appear on promotional material, including sheet music. Ramona’s image was ubiquitous, especially when the novel was turned into plays, pageants and movies, and songs were written to accompany them all.

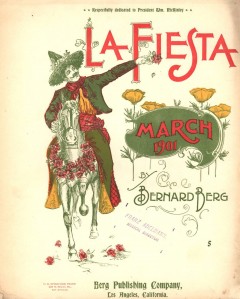

One of the biggest results of this Mexican Revival was the Fiesta de Los Angeles, an annual event that began in April 1894 and lasted until World War I. The Fiesta was the brainchild of civic leaders who wanted to take advantage of the visitors attending the 1893-94 Midwinter Fair in San Francisco. They figured they could attract a new wave of tourists to the Southland by showing off Los Angeles’ mild climate and advantages of settlement, and in so doing, they emphasized what to them was the exotic Spanish and Mexican history of Southern California. It was a huge hit. For the 1901 Fiesta, Bernard Berg, a pianist and music teacher, wrote a march, the cover for which typifies the romanticized view of Mexican Los Angeles. It shows, along with the usual poppies, a vaquero, whose likes had not been seen for decades, dressed in the Fiesta’s official colors of green, orange and red, symbolizing the dominant local agricultural products: olives, oranges and wine. The new settlers, whose agricultural pursuits had plowed under any remaining vestiges of the old cattle culture, found a way to unite these two competing forces in one image. The Broadway Department Store gave away one thousand copies of Berg’s march as a sales promotion on the opening day of the Fiesta.

One of the biggest results of this Mexican Revival was the Fiesta de Los Angeles, an annual event that began in April 1894 and lasted until World War I. The Fiesta was the brainchild of civic leaders who wanted to take advantage of the visitors attending the 1893-94 Midwinter Fair in San Francisco. They figured they could attract a new wave of tourists to the Southland by showing off Los Angeles’ mild climate and advantages of settlement, and in so doing, they emphasized what to them was the exotic Spanish and Mexican history of Southern California. It was a huge hit. For the 1901 Fiesta, Bernard Berg, a pianist and music teacher, wrote a march, the cover for which typifies the romanticized view of Mexican Los Angeles. It shows, along with the usual poppies, a vaquero, whose likes had not been seen for decades, dressed in the Fiesta’s official colors of green, orange and red, symbolizing the dominant local agricultural products: olives, oranges and wine. The new settlers, whose agricultural pursuits had plowed under any remaining vestiges of the old cattle culture, found a way to unite these two competing forces in one image. The Broadway Department Store gave away one thousand copies of Berg’s march as a sales promotion on the opening day of the Fiesta.

The romantic Mexican theme ran through much of the printed imagery of the time, especially views of the missions, and numerous tunes were written to capitalize on the popularity of California’s oldest buildings culminating in 1939 with “When the Swallows Return to Capistrano.” Tunes about the missions were popular, and their covers show a range of artistic interpretation, from outright distortion to photographic accuracy.

Apart from the popular interest in a romanticized version of local history, there was a serious effort to preserve the authentic folk songs of Mexican California. Led by Charles Lummis (1859-1928), indefatigable proponent of Southern California and the Southwest, a movement was launched not only to restore the missions, but also to save the old songs of the ranchos. In 1904, Lummis bought an Edison recorder, horn and wax cylinders and began to record and transcribe the music of a bygone era, ultimately recording over 450 songs as performed by members of the old Californio families. It took nearly twenty years to publish the results, and in 1923, his book containing fourteen of the songs appeared. As he stated: “It was barely in time; the very people who taught them to me have mostly forgotten them, or died…”

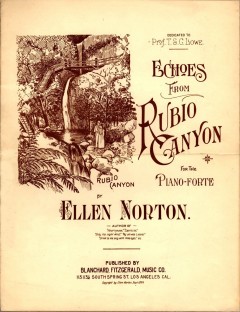

Southern California became rich in motifs, and songs were written about every aspect of tourism and settlement. The variety of flowers that grew in the Southland was a constant source of amazement to outsiders, and the native California poppy became an instantly recognizable synonym for Los Angeles that adorned book covers, sheet music, postcards and every sort of knick-knack. Resorts and hotels began to appear in songs, and did so for years, especially two of the most tourist popular destinations, Mt. Lowe and Catalina. Mt. Lowe, the creation of Thaddeus Lowe (1832-1913), aeronaut, inventor and entrepreneur, contained an engineering marvel, the Mt. Lowe Railway, which ascended from Rubio Canyon to the top of Echo Mountain in the San Gabriel Mountains above Pasadena. Lowe also built several hotels and restaurants there, including the seventy-room Echo Mountain House, completed in November 1894, and the ten-room Rubio Hotel. English pianist and composer Ellen Norton, who resided and performed in Southern California in the mid-1890s, wrote a special song interpreting the experience of the canyon, whose scenic beauty is drawn on the cover. Until it burned down in 1900, the Echo Mountain Hotel appeared on thousands of postcards and brochures, as did the Rubio Hotel, which closed in 1903. Mt. Lowe was also the subject of the “Pacific Electric Trolley Waltz” which appeared in 1906, a few years after Henry E. Huntington had purchased (and renamed) the famed funicular railway. The waltz’s cover featured a photograph of its steep incline, an image that also appeared on thousands of pieces of promotional material.

The other great resort of the time, Catalina Island, was first developed during the boom of the 1880s. The Banning Brothers, sons of pioneer citizen Phineas Banning, bought the island in 1891, making further improvements while creating an extremely attractive tourist spot and subject for yet more songs and souvenirs. When chewing gum magnate Walter Wrigley purchased the island from the Bannings in 1919, he undertook a complete redesign of the port of Avalon, making the island even more popular. Catalina reached its zenith in song when the Four Preps released their song “26 Miles (Santa Catalina)” in 1958, which went on to become a huge hit, selling over a million copies. Venice, Redondo and Coronado all had songs written about them as well, and there was barely a location in Southern California that could not boast of a song.

Music and the mild climate seemed a perfect match in Los Angeles, and much entertainment took place outdoors. The Hollywood Bowl, first used as a natural amphitheatre in 1919, became the summer home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1922. When Lloyd Wright designed its modernist acoustic shell, the Bowl became a recognizable Los Angeles icon, and of course, the subject of a song. The Song of the Hollywood Bowl had lyrics by Ahmad Sohrab, a Persian poet, diplomat and sometime rug seller active in the Baha’i movement, who, like untold others, wrote a screenplay while living in Los Angeles in the 1920s.

Across the street, the outdoor Pilgrimage Theatre (now the John Anson Ford Theater) opened in 1920 and the Greek Theatre opened in 1930. Angelenos could not get their fill of music. Nearby, outdoor pageants were performed in Hemet (The Ramona Pageant) and Palm Springs (various “Desert” plays), while Mt. Rubidoux in Riverside has been the site of outdoor Easter services since 1909. But the most popular of all the outdoor pageants was held in San Gabriel, where John S. McGroarty’s Mission Play was performed for over two decades. Opening in 1912, it ran well into the 1930s, billing itself as the corollary to Oberammergau’s Passion Play. In reality, it descended from Ramona and was an Anglo-centric, sanitized version of the Spanish Conquest of California. A paean to the Franciscan missionaries, the play’s three acts take place at three missions: San Diego, Carmel and San Juan Capistrano. As described by McGroarty, the play featured, in part, “a wonderful pageant of Indians [who] have been brought out of savagery into the full stature of civilized men.” McGroarty was also proud of the fact that many Native Californians were in the cast, stating: “A full two-thirds of the whole great cast of 100 players are natives and descendants of the old Spanish families of California.” In an astonishing collision of fact and fantasy, the Mission Play featured the daughter of an old Californio family–whose rancho figured prominently in Ramona–playing a fictional heroine inspired by Ramona. Lucretia del Valle’s (1892-1972) grandparents had settled the Camulos Ranch in 1853, and after Jackson visited it in 1884, she used it as the basis for Ramona’s Moreno Rancho. In the Mission Play, del Valle acted in over 850 performances (wearing her grandmother’s clothes) as Senora Josefa Yorba, the heroine of the third act, who was based on Ramona as well as on her own grandmother and several other women of early California. Del Valle had already appeared on the sheet music for the song about oranges in the San Gabriel Valley and she was featured on all the advertising postcards the play churned out during her years in it. On stage, “del Valle, her portrayal of Yorba, and the fictional Ramona [were collapsed] into one.”

Across the street, the outdoor Pilgrimage Theatre (now the John Anson Ford Theater) opened in 1920 and the Greek Theatre opened in 1930. Angelenos could not get their fill of music. Nearby, outdoor pageants were performed in Hemet (The Ramona Pageant) and Palm Springs (various “Desert” plays), while Mt. Rubidoux in Riverside has been the site of outdoor Easter services since 1909. But the most popular of all the outdoor pageants was held in San Gabriel, where John S. McGroarty’s Mission Play was performed for over two decades. Opening in 1912, it ran well into the 1930s, billing itself as the corollary to Oberammergau’s Passion Play. In reality, it descended from Ramona and was an Anglo-centric, sanitized version of the Spanish Conquest of California. A paean to the Franciscan missionaries, the play’s three acts take place at three missions: San Diego, Carmel and San Juan Capistrano. As described by McGroarty, the play featured, in part, “a wonderful pageant of Indians [who] have been brought out of savagery into the full stature of civilized men.” McGroarty was also proud of the fact that many Native Californians were in the cast, stating: “A full two-thirds of the whole great cast of 100 players are natives and descendants of the old Spanish families of California.” In an astonishing collision of fact and fantasy, the Mission Play featured the daughter of an old Californio family–whose rancho figured prominently in Ramona–playing a fictional heroine inspired by Ramona. Lucretia del Valle’s (1892-1972) grandparents had settled the Camulos Ranch in 1853, and after Jackson visited it in 1884, she used it as the basis for Ramona’s Moreno Rancho. In the Mission Play, del Valle acted in over 850 performances (wearing her grandmother’s clothes) as Senora Josefa Yorba, the heroine of the third act, who was based on Ramona as well as on her own grandmother and several other women of early California. Del Valle had already appeared on the sheet music for the song about oranges in the San Gabriel Valley and she was featured on all the advertising postcards the play churned out during her years in it. On stage, “del Valle, her portrayal of Yorba, and the fictional Ramona [were collapsed] into one.”

Fact and fiction had become interchangeable in Los Angeles, and the public loved their ersatz version of history. Southern California had already proven herself as fertile ground for many kinds of fictions– historical, horticultural and architectural–and this easy mingling of reality and fantasy was readily absorbed into the emerging medium of motion pictures. Los Angeles, whose protean assets were celebrated in songs and pageants, would soon become synonymous with the ultimate fantasyland, Hollywood. Johnny Mercer’s well-known song perfectly describes not only Hollywood in particular, but also Southern California in general, where American life was re-imagined, reawakened and refocused in the land of sunshine and flowers:

Hooray for Hollywood

!

That screwy, ballyhooey Hollywood!

Where any office boy or young mechanic

Can be a panic with just a good-looking pan

Where any barmaid can be a star maid

If she dances with or without a fan

Hooray for Hollywood!