GETTING WET

By Victoria Dailey

Study water; learn from water. Water isn’t afraid to change from a liquid to a gas, back to a liquid, to a solid, etc. The outward appearance of water changes but the fundamental essence of the substance remains the same. Hmm… I think there’s a lesson here.”

-Leonard Koren, Wet, No. 22, Jan-Feb 1980

Getting Wet saved me from the seventies. It arrived just as I was beginning to get really despondent about the turn the decade was taking. By 1976, most of what I regarded as the cultural achievements of the 1960s was vanishing. Disco was supplanting Woodstock as hard, glam and kitsch rockers were replacing the complicated, cryptic troubadours of consciousness and the far out. Star Wars was forcing Dr. Strangelove to act natural and the short, strange trip of the sixties was over. Hippiedom’s long hair–the ultimate symbol of a generation’s identity–was being shredded into shags. Platform shoes (only someone high on cocaine could have designed them) strutted their stuff in what was one of fashion’s most hilarious blunders. The other one was polyester. The seventies sucked.

Getting Wet saved me from the seventies. It arrived just as I was beginning to get really despondent about the turn the decade was taking. By 1976, most of what I regarded as the cultural achievements of the 1960s was vanishing. Disco was supplanting Woodstock as hard, glam and kitsch rockers were replacing the complicated, cryptic troubadours of consciousness and the far out. Star Wars was forcing Dr. Strangelove to act natural and the short, strange trip of the sixties was over. Hippiedom’s long hair–the ultimate symbol of a generation’s identity–was being shredded into shags. Platform shoes (only someone high on cocaine could have designed them) strutted their stuff in what was one of fashion’s most hilarious blunders. The other one was polyester. The seventies sucked.

So there I was, a 60s flowerette, an antiquarian, a bibliomaniac, a daydream believer, trapped in a decade that was turning out to be a total dud, a complete mockery of the sixties’ attempt to realign negative human habits. And then I got Wet, the Magazine of Gourmet Bathing. Was I stoned? High Times was one thing, but a magazine devoted to baths and bathing was a miracle because gourmet bathing was one of my pursuits! (Although, being an antiquarian, I used the term “balneology,” the study of hot baths for their therapeutic use.) Was it true, were there enough balneologists out there to sustain an entire magazine? I had already been sampling various California hot springs–Tassajara, Mercey, Paraiso, Murietta, La Vida, Soboba and Jacumba, as well as Pah Tempe in Utah– and I had even printed a card for myself that identified me as a balneologist, but when an entire magazine based on that very idea appeared, I knew that I would make it out of the dry seventies with Wet.

Soon, the magazine got even better; it seemed like some sort of quasi-New Yorker on acid. It featured really absorbing articles on ostensibly obscure topics that turned out, in hindsight, to have been way ahead of their time. Articles on skateboarding and Nikola Tesla appeared in 1979 and an article on Henry Darger in 1980, decades before the outsider artist became known to the general public.

Soon, the magazine got even better; it seemed like some sort of quasi-New Yorker on acid. It featured really absorbing articles on ostensibly obscure topics that turned out, in hindsight, to have been way ahead of their time. Articles on skateboarding and Nikola Tesla appeared in 1979 and an article on Henry Darger in 1980, decades before the outsider artist became known to the general public.

There were also interviews with seminal people, among them, Kenneth Anger whose honesty in an interview with Ann Bardach is still shocking. About Dennis Hopper he said: “Dennis is only interested in Dennis. He stole a few things from my movies…His mind is cracked. He has flashes of brilliance, but he takes too much coke and stuff.” And about Bianca Jagger he was merciless: “There are things I really dislike about the seventies. Like among women, I hate Bianca Jagger. She symbolizes everything I hate in a woman. That kind of calculating hustler.” (March-April 1980, pp. 19-21.) In the same issue, the inventor of surf music, Dick Dale, was interviewed by Kristine McKenna. It is interviews like these, with people who had notable influences on culture but who were little or under-known at the time that made Wet so brilliant. The obvious choice would have been to interview Brian Wilson or another of the Beach Boys, but Wet divined the source of the phenomenon and chose Dick Dale.

There were also interviews with seminal people, among them, Kenneth Anger whose honesty in an interview with Ann Bardach is still shocking. About Dennis Hopper he said: “Dennis is only interested in Dennis. He stole a few things from my movies…His mind is cracked. He has flashes of brilliance, but he takes too much coke and stuff.” And about Bianca Jagger he was merciless: “There are things I really dislike about the seventies. Like among women, I hate Bianca Jagger. She symbolizes everything I hate in a woman. That kind of calculating hustler.” (March-April 1980, pp. 19-21.) In the same issue, the inventor of surf music, Dick Dale, was interviewed by Kristine McKenna. It is interviews like these, with people who had notable influences on culture but who were little or under-known at the time that made Wet so brilliant. The obvious choice would have been to interview Brian Wilson or another of the Beach Boys, but Wet divined the source of the phenomenon and chose Dick Dale.

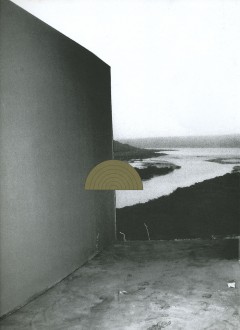

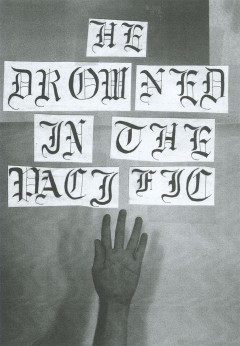

Wet had a layout that both touched on avant-garde antecedents yet was totally contemporary. Elements of Russian avant-garde typography and Surrealism are evident, but the covers, ads and contents were all presented in a new way. Much of it looks like it was computer generated, and as such, looks familiar today. But remember, Wet was produced just before computers came into wide use in the graphic arts, and some of Wet’s covers were designed by computer graphics pioneer April Greiman; the September-October 1979 cover is notable. Art and architecture were also covered, including an article on Frank Gehry in 1980 that featured the studio he designed for Ron Davis in Malibu, and a four-page spread of Ed Ruscha’s word paintings appeared in 1981.

For nearly six years, the goods kept coming. At the time, it seemed that finally, something was happening, and it was happening in Venice, Los Angeles’ seaside capital of the weird, the wired and the wise. Wet was not a New York gossip rag like Interview; it was not a San Francisco political quarterly like Ramparts: it was pure Los Angeles. It was about the body and the mind, in that order, and for good reason. Wet was like a giant wave coming to wash away all the misconceptions of the seventies, a wave that you could surf onto the shore of reawakened possibilities. By immersing the body into water heated by the earth’s internal fire the mind could float coolly upstream. And hasn’t L. A. always been about taming the unruly body in order to unlock the mind? In a coastal city of sunshine and warmth, it was inevitable. All the healers, quacks and crackpots; all the vegetarians, fruitarians and breatharians; all the wheatgrass swigging, date-shaking, crystal shining, meditating, mantra-chanting, weight-lifting, rollerblading, skateboarding and surfing acolytes who have flourished here have all used their various means to achieve the same end: to reform the body in order to free the mind. As the magazine’s publisher Leonard Koren intuited, getting wet was a good step in that direction, and that although one might immerse one’s self in an ocean wave or thermal pool, the fundamental essence of water– and its tonic properties–remains the same. Wet made that clear, and for me, studying water was good; getting Wet was better.

For nearly six years, the goods kept coming. At the time, it seemed that finally, something was happening, and it was happening in Venice, Los Angeles’ seaside capital of the weird, the wired and the wise. Wet was not a New York gossip rag like Interview; it was not a San Francisco political quarterly like Ramparts: it was pure Los Angeles. It was about the body and the mind, in that order, and for good reason. Wet was like a giant wave coming to wash away all the misconceptions of the seventies, a wave that you could surf onto the shore of reawakened possibilities. By immersing the body into water heated by the earth’s internal fire the mind could float coolly upstream. And hasn’t L. A. always been about taming the unruly body in order to unlock the mind? In a coastal city of sunshine and warmth, it was inevitable. All the healers, quacks and crackpots; all the vegetarians, fruitarians and breatharians; all the wheatgrass swigging, date-shaking, crystal shining, meditating, mantra-chanting, weight-lifting, rollerblading, skateboarding and surfing acolytes who have flourished here have all used their various means to achieve the same end: to reform the body in order to free the mind. As the magazine’s publisher Leonard Koren intuited, getting wet was a good step in that direction, and that although one might immerse one’s self in an ocean wave or thermal pool, the fundamental essence of water– and its tonic properties–remains the same. Wet made that clear, and for me, studying water was good; getting Wet was better.