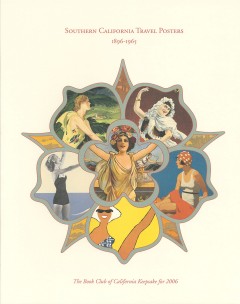

From Ramona To Gidget: Southern California Travel Posters 1896-1965

by Victoria Dailey

Preface

Preface

California has never been at a loss for heroines. Her very name is said to have derived from a woman–the mythical Queen Califia –and over three centuries later, when California entered the Union in 1850, Minerva, the warrior goddess of wisdom, poetry and music, was chosen as the official state symbol. Although named for a queen and symbolized by a goddess, California has produced other feminine luminaries of more modest origins: two of the most popular have been a mixed-race girl and an L. A. teen-ager. Their humble beginnings did not prevent them from capturing the imagination of generations and influencing many aspects of California culture. Each of these avatars came to represent the Golden State and a way of envisioning her. Ramona, the first of these California Goddesses, was Helen Hunt Jackson’s tragic heroine of the novel of the same name, first published in 1884. The second is Gidget, the heroine of the novella written by Frederick Kohner, first published in 1957. Neither of these archetypal California Girls was created by a native Californian–Jackson was a New Englander and Kohner, a Czech-Jewish émigré. Nevertheless, each writer created an enduring symbol of Southern California, which was one of the most heavily advertised places on earth at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, and countless brochures, souvenirs and posters feature some incarnation of Ramona as a Southland symbol, whether it is a charming señorita, Franciscan padre or Spanish mission. Later advertising often focuses on a Gidget-like beach girl. When Ramona or Gidget are not featured, other women often are: sometimes she is the goddess Flora, often she is an idealized woman. In any case, artists often depict California, the realm of Queen Califia, as a woman, and in the fourteen posters presented in this keepsake, women are prominent in nine of them. They span California’s feminine iconography from Ramona to Gidget.

I: Romance of the Ranchos

Ramona, the half-Indian, half-Spanish daughter of the early California ranchos, was supposed to bring the plight of California’s Indians to the attention of the American public. Instead, she became the beautiful and brave señorita of a romanticized past, an emblem of a vanished culture, a fictional girl turned into a myth. She provided a society in search of a culture the seed of one. Suddenly, in a Ramona-induced craze, Southern Californians, (mainly Protestant Yankees), appropriated and revived the Spanish and Mexican Catholic traditions of old California. The crumbling 18th century missions were restored. Spanish architecture became the norm, replacing the American vernacular styles of Queen Anne and Beaux-Arts. Los Angeles began to hold a Mexican fiesta in the 1890s, and much of the California tourist industry involved excursions to sites mentioned in Ramona.

Jackson’s timing could not have been better planned. Ramona appeared just before the huge Southern California land boom of the late 1880s. The direct railroad route to Los Angeles was completed in 1885 and tourists and settlers poured into the region. Many of them had read Ramona and were eager to see the locales depicted in the novel. Although Jackson had fictionalized her settings, an entire industry arose around places supposed to have been the ones she described. The old Estudillo adobe in San Diego was touted as “Ramona’s Wedding Place.” The Rancho Camulos in Ventura County was thought to have been “The Home of Ramona.” Tourists adored visiting these “shrines.” Soon, actual places began to imitate art: The San Diego County town of Nuevo changed its name to Ramona in 1886. Ramona was on a roll. Mary Pickford played her in a 1910 movie, as did Loretta Young in 1936. Since 1923 a Ramona Pageant has been held every spring in Hemet, where Raquel Welch played our heroine in 1959. Ramona swept across Southern California, and Ramona transmogrified from heroine to myth.

After Ramona was first published in 1884, it wasn’t long before her likeness began to appear in popular imagery. Her image, that of a young woman in Spanish or Mexican dress, was used on orange and lemon crate labels in the burgeoning citrus industry, and she appeared on brochures and guidebooks, and in posters. One of the earliest posters produced in Los Angeles was for the 1896 Fiesta de Los Angeles, and prominent on it is the Ramona image, a dancing girl wearing a lace mantilla who beckons visitors to the annual event first held in 1894. Southern California began to hold small outdoor fairs to celebrate its mild climate and attract settlers in the 1880s, and by the 1890s, Los Angeles was known as a tourist’s paradise. A city festooned with flowers the year round, with orange groves and gardens everywhere, Los Angeles was advertised to the world in printed matter of all forms. In poster after poster, Los Angeles and Southern California were advertised for their horticultural, agricultural and outdoor wonders. Where else could a rose festival be held on January 1? Where else could an air show be held in the middle of winter? Where else could an orange show be held in February? Southern California was unlike any other place in the nation, and artists and designers ably demonstrated the region’s virtues in eye-catching, colorful posters. Hispanic themes derived from Ramona were natural. Ramona’s architectural influence may be seen in the posters for the San Diego Exposition of 1916, the San Diego Exposition of 1935 and the United Air Lines poster featuring the Santa Barbara Mission.

II: I Wish They All Could Be California Girls

II: I Wish They All Could Be California Girls

California’s other main heroine, Gidget, whom I have dubbed The Venus of Malibu, arrived not on a seashell but on a surfboard, and created a sea change. Gidget’s influence has been titanic, launching an international surf culture, a movie franchise, an American argot, a popular music style, and a California archetype. Furthermore, the ecological awareness of the ocean and the various groups that have been organized to save it may also trace their origins, at least in part, to Gidget.

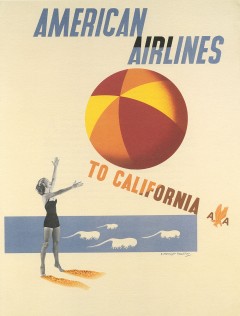

Her creator, Frederick Kohner, came to California as a Jewish refugee. Born in Czechoslovakia, he wrote screenplays in the German film industry and fled the Nazis in the early 1930s. Arriving in Hollywood, he found work as a screenwriter, and was nominated for an Academy Award in 1938. Kohner, his wife and children lived near Malibu where his teenage daughter, Kathy, developed an interest in surfing. Kohner found her tales of beach and surfing life intriguing enough to turn into a book and the title derives from the nickname the surfers coined for Kathy Kohner, a contraction of “girl midget.” Gidget became the new archetype of the California Girl, a wholesome lover of fun and the sun, a girl not afraid of risks, a girl who could challenge the masculine world around her while becoming one of the boys. Girls at the beach were certainly common themes in posters designed to attract visitors to California, but with Gidget, the beach girl changed. Compare Maurice Logan’s pre-Gidget 1923 image to the post-Gidget one in the Santa Fe poster of 1965. A demure lass has become an insouciant beach chick, a girl just like Gidget. Kauffer’s spectacular image of 1947 also features a beach girl, but the main image in his poster is not the girl but a beach ball. The California beach girl image crystallized in Gidget, and the 1959 movie based on the book, changed California (and American) culture profoundly. Surf Culture sprang directly from Gidget, and among her progeny are the Beach Boys and the entire surf sound, surf movies, surf fashion (including flip-flops, now more popular than ever), surf lingo (kowabunga, dude!), surf magazines, the multi-million dollar surfboard industry, international surfing contests, and even skateboarding, a form of surfing for the landlocked. The final image in this keepsake is a truly Gidget-inspired one, and Gidget has been a strong visual type for nearly half a century.

III: Girls into Goddesses

Curiously, neither Ramona nor Gidget are great works of literature. Although Jackson’s physical descriptions of the Southern California landscape are superb, Ramona’s story and style do not appeal to today’s readers. Its creaky plot, 19th century phraseology and Victorian sensibilities seem extremely outdated, yet the heroine Jackson created has transcended the confines of her literary circumstances. Ramona became an enduring symbol for the emerging culture of Southern California, and her influence has been vast. Similarly, although the literary merits of Gidget are minor, millions have understood the message Gidget offered. Her influence on style is obvious, but substance accidentally followed in her wake. To surf is to give one’s self up to the lure and power of the ocean, to get in sync with the rhythm of the waves, to become part of the natural world for a few quick seconds. The search for such experiences, so Californian in their attachment to and love for nature, has been Gidget’s deeper legacy. As a surfer girl, she became a role model and launched a style, but in her secret role as a sea goddess, The Venus of Malibu effected more profound change.