A Ladies’ Dozen And A Gentleman: Early California Children’s Books 1853-1913

By Victoria Dailey

Books for children flowered during the 19th century, when Victorian society began to encourage the education and imagination of its youngest members. (I am using the word “children” to refer to youngsters up to the age of twelve.) Of course, children’s books and other pedagogical materials–hornbooks and battledores–had existed since the dawn of printing, but as the middle class became more affluent during the Industrial Revolution, children began to be educated in large numbers so that they could become useful, well-rounded members of an expanding society. As a result, their reading needs began to grow from merely the ABCs and musty moral lessons to vivid stories, tender tales and amusing antics. Forward-thinking parents encouraged their children’s reading habits and bestowed upon them many a present in the form of a book. Out of this milieu came such classic works as Alice in Wonderland (1865); Heidi (1880); Uncle Remus (1881); A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885); Goops and How to Be Them (1900); Tales of Peter Rabbit (1902); and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1906).

Books for children flowered during the 19th century, when Victorian society began to encourage the education and imagination of its youngest members. (I am using the word “children” to refer to youngsters up to the age of twelve.) Of course, children’s books and other pedagogical materials–hornbooks and battledores–had existed since the dawn of printing, but as the middle class became more affluent during the Industrial Revolution, children began to be educated in large numbers so that they could become useful, well-rounded members of an expanding society. As a result, their reading needs began to grow from merely the ABCs and musty moral lessons to vivid stories, tender tales and amusing antics. Forward-thinking parents encouraged their children’s reading habits and bestowed upon them many a present in the form of a book. Out of this milieu came such classic works as Alice in Wonderland (1865); Heidi (1880); Uncle Remus (1881); A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885); Goops and How to Be Them (1900); Tales of Peter Rabbit (1902); and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1906).

Concomitant with this expansion of books intended for children was a rise in the number of women writers, many of who wrote specifically for children. Women often turned to writing out of economic necessity, finding themselves widowed or abandoned, usually with children to support. Writing joined the ranks of acceptable careers for women after teaching and nursing, and many were successful at it. In fact, one of the earliest and best accounts of the Gold Rush was written by a woman, Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe (1819–1906), whose Shirley Letters (1854-55) were published under the pseudonym “Dame Shirley.” It became the source for many later works of fiction and history, and writers from Bret Harte to Hubert Howe Bancroft, and possibly even Samuel Clemens, owe a debt to Clappe and her remarkable powers of observation.

By the time of the Gold Rush, children in the United States enjoyed a wide variety of books intended solely for their education and pleasure, and children in California were no exception–they read the same books as their American cousins–yet when California entered the Union in 1850, books for children with California themes did not exist. There were no works of fiction about California–accounts had been written as narratives for adults. But with the Gold Rush came the emergence of California as a subject for literary interpretation, and slowly California entered the world of fiction. One of the earliest bits of California juvenilia was The Adventures of Mr. Tom Plump, an 8-page chapbook published in New York by Huestis & Cozans, c. 1852. Several years later, circa 1855, the anonymously published Allen Crane: the Gold Seeker appeared, but it contained only one story about the Gold Rush among its tales and poems. Hutchings & Rosenfield’s Uncle John’s Stories for Good California Children (1860) also contained only one California tale, and it was only partially set there–the mention of California in the title was mainly promotional. Alice Bradley Haven’s All’s Not Gold that Glitters (1853) therefore, has the distinction of being among the earliest, if not the first book, written for children about California and the Gold Rush.

By the time of the Gold Rush, children in the United States enjoyed a wide variety of books intended solely for their education and pleasure, and children in California were no exception–they read the same books as their American cousins–yet when California entered the Union in 1850, books for children with California themes did not exist. There were no works of fiction about California–accounts had been written as narratives for adults. But with the Gold Rush came the emergence of California as a subject for literary interpretation, and slowly California entered the world of fiction. One of the earliest bits of California juvenilia was The Adventures of Mr. Tom Plump, an 8-page chapbook published in New York by Huestis & Cozans, c. 1852. Several years later, circa 1855, the anonymously published Allen Crane: the Gold Seeker appeared, but it contained only one story about the Gold Rush among its tales and poems. Hutchings & Rosenfield’s Uncle John’s Stories for Good California Children (1860) also contained only one California tale, and it was only partially set there–the mention of California in the title was mainly promotional. Alice Bradley Haven’s All’s Not Gold that Glitters (1853) therefore, has the distinction of being among the earliest, if not the first book, written for children about California and the Gold Rush.

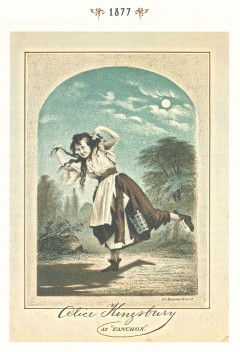

The 1860s saw a rise in the number of books for children with California as a backdrop, and after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, the expansion of the California population resulted in more interest and a greater demand for books with California subject matter. California now had twenty years of statehood, and as people began to look back to the Gold Rush with nostalgia and wonder, stories for adults and children started to appear about the doings in the mines. Bret Harte began to publish his work in the Overland Monthly, and Samuel Clemens used his sojourn in California in the 1860s as the basis for many of his works. “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” became the title story in his first book, published in 1867. Little known and poorly remembered, other books about California were also written at this time, works intended solely for children. Written mainly by women, these works enjoyed great popularity in their day and included among these authors was a leading actress, Alice Kingsbury; one of the first female journalists, Carrie Carlton; and a respected poetry editor, May Wentworth. Although they, and many others of their time, are no longer well known, they found a champion in Ella Sterling Cummins Mighels, who captured their biographies and assessed their abilities in her pioneering work The Story of the Files (1893). Without Mighels, much of this literary history would be lost, and Mighels may be considered California’s first literary historian and promoter of women writers.

Although they wrote the majority, women did not write all the books in this keepsake: among these dozen ladies is one sole man, Henry Lathrop Turner, who wrote a charming work for children, In the Lovely Land of Sunset (1886). This unusual production is similar in spirit to Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses, and they appeared within a year of each other. Turner focuses solely on Santa Barbara as the inspiration for his poems and stories, which have children as their main characters. Santa Barbara became a popular subject in California travel writing in the late 19th century, but this is the only such work of the period written for children.

Although they wrote the majority, women did not write all the books in this keepsake: among these dozen ladies is one sole man, Henry Lathrop Turner, who wrote a charming work for children, In the Lovely Land of Sunset (1886). This unusual production is similar in spirit to Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses, and they appeared within a year of each other. Turner focuses solely on Santa Barbara as the inspiration for his poems and stories, which have children as their main characters. Santa Barbara became a popular subject in California travel writing in the late 19th century, but this is the only such work of the period written for children.

By the 1880s, especially after that decade’s boom in real estate, California was known throughout the world and became a popular topic for the reading public, children included. Although her fame rests on Ramona, Helen Hunt Jackson wrote many works for children, including The Hunter Cats of Connorloa (1884), a story based on events at Kinneloa, her friend Abbot Kinney’s ranch near Pasadena; it appeared in the same year as Ramona. Another noted writer, Mary Austin, also wrote a book for children, The Basket Woman (1904). Her goal was to present Native Americans to children in a positive light, similar in spirit to Jackson’s Ramona. The 1890s saw an increase in interest in California’s ethnic populations, and works on San Francisco’s Chinese community began to appear, including Mary Bamford’s Ti: A Story of San Francisco’s Chinatown (1899). Also published in 1899 was Docas, the Indian Boy of Santa Clara by Genevra Sisson Sneddon, which shed a sympathetic light on California’s Native Americans and became a standard work in elementary school curricula for decades.

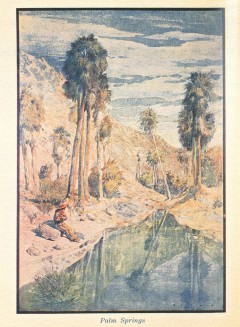

California was frequently promoted as a paradise for children to parents everywhere, and children themselves began to enjoy the newly written books set in the Golden State, books written especially for them. Taking place throughout California, from San Francisco to Yosemite, from Fresno to Inyo, and from San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara to Los Angeles and the desert, California children’s books, and particularly those in this keepsake, cover a wide geographic range and present people from a variety of backgrounds. Through them, children began to absorb California’s past and encounter people and places they might never visit but could readily imagine. These pioneering works presented California to young readers for the first time, and they are noteworthy additions to the literary bibliography of the Golden State.

California was frequently promoted as a paradise for children to parents everywhere, and children themselves began to enjoy the newly written books set in the Golden State, books written especially for them. Taking place throughout California, from San Francisco to Yosemite, from Fresno to Inyo, and from San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara to Los Angeles and the desert, California children’s books, and particularly those in this keepsake, cover a wide geographic range and present people from a variety of backgrounds. Through them, children began to absorb California’s past and encounter people and places they might never visit but could readily imagine. These pioneering works presented California to young readers for the first time, and they are noteworthy additions to the literary bibliography of the Golden State.